Chinese Dialects: The Essential Guide for Travelers to China

China’s linguistic landscape presents a fascinating challenge for travelers. What many call “Chinese” is actually a family of languages with remarkable diversity. In my 12 years guiding tours across China, I’ve witnessed countless visitors surprised by the country’s linguistic complexity.

Understanding Chinese dialects enhances your travel experience immensely. This guide will walk you through what you need to know about Chinese language diversity before your journey begins.

The sheer scale of China’s linguistic diversity rivals that of Europe. Imagine traveling from Rome to Oslo and encountering a dozen distinct languages along the way. China presents a similar linguistic journey within a single national border. Each dialect tells the story of regional history, migrations, invasions, and cultural exchanges spanning thousands of years.

Table of Contents

Understanding Chinese Dialects: Beyond Mandarin

When planning your trip to China, knowing about linguistic diversity helps you navigate with confidence. China isn’t just home to one language but a rich tapestry of dialects.

These aren’t mere accent variations. Many Chinese “dialects” are mutually unintelligible languages. A Cantonese speaker from Guangzhou might struggle to understand a Mandarin speaker from Beijing.

Chinese dialects belong to the Sino-Tibetan language family. They share writing systems and cultural heritage but differ dramatically in pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar.

The Major Chinese Dialect Groups

China recognizes seven major dialect groups. Each contains numerous sub-dialects that vary by region, city, and sometimes even between neighboring villages.

1. Mandarin (官话 – Guānhuà)

Mandarin dominates northern and southwestern China. About 70% of Chinese speakers use it as their mother tongue. This dialect group includes:

- Standard Mandarin (普通话 – Pǔtōnghuà): China’s official language

- Northeastern Mandarin (东北话 – Dōngběihuà): Spoken in Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning

- Beijing Mandarin (北京话 – Běijīnghuà): The basis for Standard Mandarin

- Southwestern Mandarin (西南官话 – Xīnán Guānhuà): Common in Sichuan, Yunnan, and Guizhou

During my tours in Beijing, I’ve noticed most visitors can get by with basic Mandarin phrases. The government’s promotion of Standard Mandarin means you’ll find Mandarin speakers virtually everywhere.

2. Wu (吴语 – Wúyǔ)

Wu dialects thrive around Shanghai, Zhejiang, and parts of Jiangsu. About 80 million people speak Wu varieties.

Shanghainese (上海话 – Shànghǎihuà) is the most famous Wu dialect. Its distinctive tones and vocabulary make it incomprehensible to Mandarin speakers.

A client once told me she was baffled when her Mandarin-speaking guide couldn’t understand elderly locals in a Shanghai side street. This illustrates how different these linguistic systems truly are.

3. Yue (粤语 – Yuèyǔ)

Cantonese (广东话 – Guǎngdōnghuà) is the most prominent Yue dialect. It’s widespread in:

- Guangdong province

- Hong Kong

- Macau

- Parts of Guangxi

- Many overseas Chinese communities

Cantonese preserves more features of ancient Chinese than Mandarin. Its nine tones (compared to Mandarin’s four) create a melodic quality many visitors find distinctive.

When I lead tours in Hong Kong, I notice tourists appreciating locals who switch between Cantonese and English. However, in more rural Guangdong areas, Cantonese dominates completely.

4. Min (闽语 – Mǐnyǔ)

Min dialects appear in Fujian province, Taiwan, Hainan, and parts of Southeast Asia. They include:

- Hokkien (福建话 – Fújiànhuà): Common in southern Fujian, Taiwan, and Southeast Asia

- Teochew (潮州话 – Cháozhōuhuà): Spoken in eastern Guangdong

- Taiwanese Hokkien (台湾话 – Táiwānhuà): The everyday language of many Taiwanese people

Min dialects retained many archaic features. They diverged from other Chinese varieties earliest, making them particularly distinct.

5. Hakka (客家话 – Kèjiāhuà)

Hakka means “guest families,” reflecting the historical migration of its speakers. Hakka people moved from northern China to the south centuries ago, preserving their distinct language.

You’ll find Hakka speakers in:

- Parts of Guangdong

- Fujian

- Jiangxi

- Taiwan

- Southeast Asia

During a village homestay in Fujian, I watched a Hakka grandmother teaching her grandchild traditional songs. This cultural transmission through language happens across China.

6. Xiang (湘语 – Xiāngyǔ)

Hunan province is home to Xiang dialects. About 38 million people speak these varieties.

Xiang combines elements of both northern and southern Chinese. Its subtypes include Old Xiang and New Xiang, with the latter showing more Mandarin influence.

7. Gan (赣语 – Gànyǔ)

Jiangxi province and neighboring areas host Gan dialects. Like Hakka and Xiang, Gan preserves many ancient Chinese features while developing unique characteristics.

The Language vs. Dialect Debate

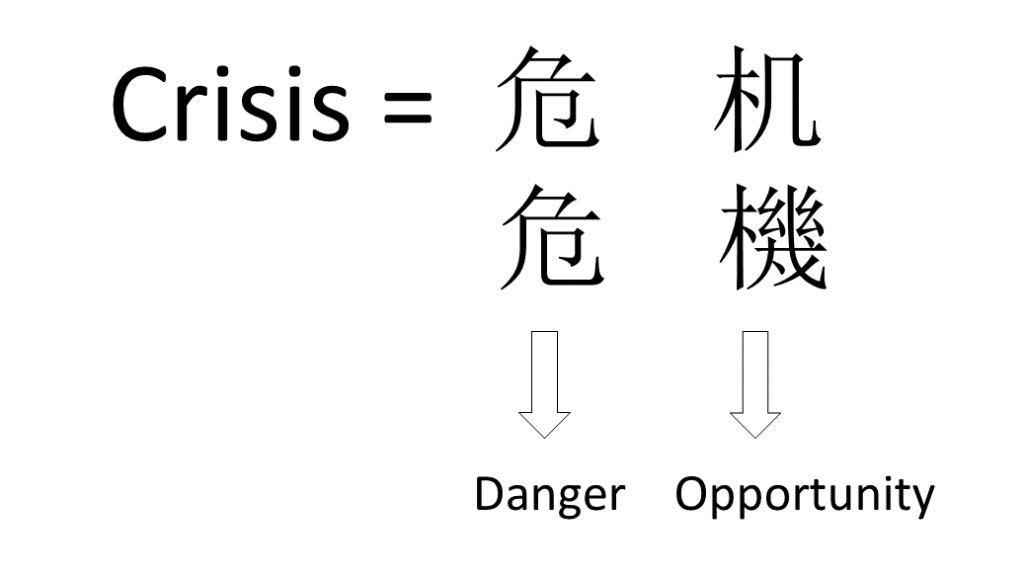

Linguists often cite the aphorism: “A language is a dialect with an army and navy.” This highlights how political factors influence language classification.

Chinese varieties differ more than Romance languages like Spanish and Italian. Yet political and cultural unity encourages classifying them as “dialects” rather than separate languages.

For travelers, the distinction matters little. What’s important is recognizing the communication challenges you might face in different regions.

The Role of Standard Mandarin

In 1955, the Chinese government established Standard Mandarin (普通话 – Pǔtōnghuà) as the official language. Based on Beijing dialect, it serves as China’s lingua franca.

All Chinese schools teach Standard Mandarin. Public broadcasts, national media, and government communications use it exclusively.

This standardization helps travelers tremendously. Young Chinese people typically speak Standard Mandarin regardless of their native dialect. In tourist areas, expect service staff to communicate in Mandarin.

The Standardization Process

The standardization of Mandarin involved several key phases:

- Initial reform (1955-1960): Establishment of Putonghua as the standard and introduction of simplified characters

- Cultural Revolution impact (1966-1976): Disruption of linguistic research but continued promotion of standard language

- Revival period (1978-present): Renewed emphasis on national language standardization

The government’s Promotion of Putonghua campaign continues today. Annual surveys measure standard language adoption rates, which now exceed 80% nationwide. Urban centers show rates above 90%, while rural areas demonstrate greater dialect preservation.

Every September 16th marks “Promote Putonghua Day,” with educational events nationwide. Schools hold speech competitions and media outlets feature special programming about language standardization.

Written Chinese: The Great Unifier

Despite spoken differences, written Chinese creates unity. Most Chinese dialects share the same writing system.

A Cantonese speaker from Hong Kong and a Mandarin speaker from Beijing might struggle in conversation. Yet they can communicate perfectly through writing.

However, two writing systems exist:

- Simplified Chinese: Used in mainland China and Singapore

- Traditional Chinese: Used in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau

Simplified characters, introduced in the 1950s, have fewer strokes, making them easier to learn and write. Traditional characters preserve historical forms.

Character Evolution and Structure

Chinese characters evolved over 5,000 years from pictographs to today’s complex system. Understanding their basic structure helps travelers recognize patterns:

- Pictographs (象形 xiàngxíng): Direct representations of objects (山 shān – mountain)

- Ideographs (指事 zhǐshì): Abstract concepts (上 shàng – up, 下 xià – down)

- Compound ideographs (会意 huìyì): Combined meanings (明 míng – bright, combines 日 rì – sun and 月 yuè – moon)

- Phono-semantic compounds (形声 xíngshēng): Sound and meaning elements together (约 90% of modern characters)

Most modern Chinese characters combine a semantic component (radical) suggesting meaning and a phonetic component suggesting pronunciation. For example, 妈 (mā – mother) combines the female radical 女 with the phonetic element 马 (mǎ).

Written Dialect Variations

While standard written Chinese predominates, some interesting variations exist:

- Cantonese-specific characters: Characters unique to Cantonese that don’t exist in standard written Chinese

- Taiwanese characters: Special characters developed for writing Taiwanese Hokkien

- Regional variants: Character forms that evolved separately in different regions

In Hong Kong bookstores, I’ve browsed Cantonese novels containing characters no Mandarin reader would recognize. These specialized characters capture sounds unique to Cantonese.

Practical Travel Tips for Navigating Chinese Dialects

Where Will Your Dialect Knowledge Matter Most?

Based on my experience guiding tours, here’s where dialect awareness matters most:

- Hong Kong and Macau: Cantonese dominates daily life though English works in tourist areas

- Taiwan: Mandarin is official, but Taiwanese Hokkien is common in everyday settings

- Shanghai: While Mandarin works everywhere, knowing basic Shanghainese phrases delights locals

- Rural areas: Local dialects prevail, and fewer people speak Mandarin fluently

Linguistic Map of Tourist Destinations

Understanding the dialect geography helps plan your communication strategy:

| Region | Primary Dialect | Secondary Languages | English Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | Mandarin | English in tourist sites | Moderate-High |

| Shanghai | Wu (Shanghainese) | Mandarin, English | High |

| Xi’an | Mandarin (Shaanxi accent) | English in tourist sites | Moderate |

| Guangzhou | Cantonese | Mandarin | Low-Moderate |

| Hong Kong | Cantonese | English, Mandarin | High |

| Chengdu | Southwestern Mandarin | Standard Mandarin | Low-Moderate |

| Kunming | Southwestern Mandarin | Local minority languages | Low |

| Lhasa | Tibetan | Standard Mandarin | Low |

| Urumqi | Uyghur | Standard Mandarin | Low |

Learning Basics: Focus on Mandarin

For most travelers, learning some Mandarin basics makes the most sense. Even in regions where local dialects dominate, Mandarin serves as a bridge language.

Start with these essential phrases:

- 你好 (Nǐ hǎo) – Hello

- 谢谢 (Xièxie) – Thank you

- 请 (Qǐng) – Please

- 对不起 (Duìbùqǐ) – Sorry

- 多少钱 (Duōshǎo qián) – How much?

Dig deeper: Survival Chinese: Essential Phrases for Travelers

Pronunciation Challenges

Chinese tonal systems present particular challenges for English speakers. Here’s a quick guide to Mandarin’s four tones:

- First tone (ˉ): High and level (mā – mother)

- Second tone (ˊ): Rising (má – hemp)

- Third tone (ˇ): Falling then rising (mǎ – horse)

- Fourth tone (ˋ): Sharp falling (mà – scold)

Cantonese presents even greater complexity with its six to nine tones (depending on classification systems). This tonal richness contributes to Cantonese’s musical quality but increases learning difficulty.

Using Technology to Bridge Dialect Gaps

Translation apps help tremendously. I recommend:

- Pleco: The gold standard Chinese dictionary app

- Baidu Translate: Works better within China than Google Translate

- WeChat: Its translation feature works well for daily communication

- Hanping: Excellent for Cantonese specifically

- Zhongwen: A pop-up dictionary that helps read Chinese characters

Many of my clients download regional phrasebooks before visiting dialect-heavy areas like Guangdong or Fujian.

Body Language and Non-Verbal Communication

When language fails, non-verbal communication becomes crucial. Some tips:

- Use your fingers to indicate numbers (but note different finger counting methods)

- Carry a pen and paper for drawing or writing numbers

- Show pictures of destinations to taxi drivers

- Use map apps with Chinese character display

- Learn basic Chinese gestures (which sometimes differ from Western ones)

On my tours, I teach clients the “point at menu” technique with a respectful nod. This universally understood method works across all dialect regions.

Regional Dialect Experiences for Travelers

Mandarin Regions (Beijing, Xi’an, Chengdu)

In Beijing, the birthplace of Standard Mandarin, accent differences still exist. Locals often add an “er” sound to words (known as erhua) and have distinctive pronunciations.

Xi’an locals speak a form of Mandarin with noticeable differences from the standard. However, tourism workers speak excellent Standard Mandarin.

Chengdu’s Southwestern Mandarin features unique vocabulary and a melodic quality many visitors find charming. The relaxed pace matches the city’s laid-back lifestyle.

Wu Region (Shanghai, Hangzhou, Suzhou)

In Shanghai, I’ve observed the generational language shift. Older people often prefer Shanghainese, while younger generations switch effortlessly between Wu and Mandarin.

Luxury boutiques in Shanghai often hire staff proficient in multiple languages, including English, Japanese, and Korean, alongside Mandarin and Shanghainese.

Hangzhou and Suzhou each have distinct Wu varieties. These ancient cities preserve linguistic traditions alongside their cultural heritage.

Cantonese Region (Guangzhou, Hong Kong, Macau)

Hong Kong offers a linguistic feast. Cantonese dominates, but English remains widely spoken in tourist areas. Restaurant menus typically appear in Chinese, English, and sometimes other languages.

In Guangzhou, traditional Cantonese opera thrives, preserving classical language forms. The city’s linguistic landscape reflects its trading history and international connections.

Macau adds Portuguese influence to its primarily Cantonese foundation. Street signs appear in Chinese, Portuguese, and English, creating a unique linguistic atmosphere.

Min Region (Xiamen, Taipei)

Xiamen (Amoy) in Fujian province features Southern Min dialects. The city’s island location helped preserve its distinctive language throughout history.

In Taipei, government signage appears in Mandarin, but Taiwanese Hokkien conversations fill traditional markets. This linguistic duality reflects Taiwan’s complex history.

Hakka Regions (Meizhou, Hakka Tulou)

The Hakka tulou (earthen buildings) in Fujian provide immersive experiences in Hakka culture and language. These UNESCO sites preserve centuries-old linguistic traditions.

In Meizhou, Guangdong’s “Hakka Capital,” language preservation efforts include cultural festivals and educational programs. Visitors can experience authentic Hakka cuisine while hearing the distinctive language.

Cultural Expression Through Dialects

Chinese Opera Traditions

Chinese opera forms reflect regional dialects beautifully:

- Beijing Opera uses stylized Mandarin

- Cantonese Opera preserves ancient Cantonese

- Yue Opera from Zhejiang features Wu dialect elements

Each opera tradition maintains unique linguistic features, even as everyday language evolves. Attending performances provides cultural and linguistic insights.

Regional Literature and Poetry

Classical Chinese literature often incorporates dialect elements. Modern Chinese literature increasingly embraces dialect diversity, preserving regional expressions and storytelling styles.

Writers like Lu Xun and Mo Yan incorporate dialect terms that capture concepts untranslatable in Standard Mandarin. This linguistic richness reflects China’s cultural depth.

Music and Modern Media

Popular music showcases dialect diversity. Cantonese pop (Cantopop) from Hong Kong achieved international recognition. Hokkien songs remain popular in Taiwan, while Shanghai produces distinctive Wu-language music.

Television programs increasingly feature dialect content. Period dramas often use regional languages for authenticity, while comedy shows leverage dialect humor.

The Future of Chinese Dialects

Urbanization and media standardization threaten dialect diversity. Young people increasingly prefer Mandarin for education and career advancement.

However, cultural preservation efforts are growing:

- Dialect preservation societies document endangered varieties

- Apps and websites teach traditional expressions

- Some schools offer dialect classes alongside standard curriculum

During a recent tour in Guangzhou, I visited a community center hosting Cantonese language classes for children of Mandarin-speaking migrants. This demonstrates growing recognition of dialect importance.

Academic Preservation Efforts

Linguistic researchers are racing to document endangered dialect varieties:

- Dialect Atlases: Comprehensive mapping projects record pronunciation variations across regions

- Audio Archives: Digital recordings preserve speech patterns of elderly dialect speakers

- Linguistic Fieldwork: Researchers document grammar and vocabulary of lesser-known varieties

- Computational Analysis: Modern algorithms help track dialect evolution and relationships

The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences leads national dialect preservation efforts. Their Linguistic Atlas of Chinese Dialects project has documented over 2,500 dialect points across China.

Universities worldwide contribute to this work. The University of Washington’s Chinese Dialect Geography project uses GIS technology to map dialect boundaries with unprecedented precision.

Digital Revival

Technology plays a crucial role in dialect preservation:

- Social Media: Dialect hashtags trend as young people embrace linguistic heritage

- Video Platforms: Content creators produce dialect-learning videos attracting millions of views

- Mobile Apps: Interactive learning tools teach dialect phrases to new generations

- AI Voice Recognition: Systems increasingly accommodate dialect variations

The “Speak Shanghainese” WeChat mini-program launched in 2022 has over two million users. Similar applications exist for Cantonese, Hokkien, and Hakka, reflecting growing interest in dialect preservation.

Policy Developments

Government attitudes toward dialects have evolved:

- Early PRC Period (1950s-1980s): Strong emphasis on Mandarin standardization

- Reform Era (1980s-2000s): Relaxed attitude allowing some dialect media

- Recent Developments (2010s-present): Recognition of dialects as cultural heritage

The 2017 “Linguistic Resources Protection Project” marked a significant policy shift. It allocated funding for dialect documentation and established protected dialect zones in regions with endangered linguistic varieties.

UNESCO’s recognition of certain Chinese dialect traditions as Intangible Cultural Heritage has further elevated their status.

Embracing Linguistic Diversity as a Traveler

China’s linguistic tapestry offers unique insights into its cultural complexity. Each dialect carries centuries of history, reflecting regional identity and collective memory.

As a traveler, approaching this diversity with curiosity enhances your journey. Even learning a few local phrases demonstrates respect for regional culture.

My clients consistently report deeper connections with local communities when they make efforts to understand dialect differences. These moments—whether ordering in a local restaurant or chatting with artisans—often become trip highlights.

Preparing for Your Language Journey Across China

Before visiting China, consider:

- Learning basic Mandarin phrases for everyday situations

- Downloading translation apps that work without internet

- Researching specific expressions used in your destination regions

- Keeping a pocket phrasebook for regions where your dialect might differ

On our Travel China With Me tours, we provide regional language cards with essential phrases in local dialects. These small efforts create meaningful cultural bridges.

Case Study: A Linguistic Journey Through China

Let me share a recent experience guiding the Zhang family—overseas Chinese Americans returning to explore their ancestral heritage. Their journey illustrates how dialect awareness transforms a China trip:

Beijing (Mandarin Region) The family arrived in Beijing, where Standard Mandarin dominates. Mr. Zhang, fluent in Mandarin, navigated easily. His teenage children, with basic Mandarin, quickly gained confidence ordering food and asking directions.

Xi’an (Northwestern Mandarin) In Xi’an, they encountered stronger accents and regional expressions. Local guides explained how Xi’an dialect preserves elements of ancient Chang’an speech patterns from the Tang Dynasty. The family learned phrases like “biang biang noodles”—a local specialty with a character so complex it’s not in standard keyboards.

Shanghai (Wu Region) The linguistic landscape shifted dramatically in Shanghai. Mrs. Zhang’s grandmother had been Shanghainese, and she recognized fragments of phrases from childhood. The family visited the Shanghai Dialect Museum, where interactive displays demonstrated how Wu dialects preserved sounds lost in Mandarin centuries ago.

Guangzhou (Cantonese Region) In Guangzhou, Mr. Zhang’s ancestral hometown, the family experienced complete linguistic transformation. Though sharing written characters with other regions, spoken Cantonese required different communication strategies. Mr. Zhang’s childhood Cantonese returned slowly during their week there. The children recorded elderly relatives sharing family stories, preserving both heritage and dialect for future generations.

Fujian Countryside (Min Region) Their final stop in rural Fujian connected them with Mrs. Zhang’s paternal village. Here, elderly relatives spoke Eastern Min dialect exclusively. Communication relied on a local interpreter translating between Min and Mandarin. The village temple preserved ancient ritual texts in classical Chinese with Min pronunciation guides—a living museum of linguistic history.

This family’s journey exemplifies how dialect awareness deepens cultural connection. Each region offered not just different sights but different soundscapes—each with centuries of history embedded in tones and vocabulary.

Conclusion: The Richness of Chinese Linguistic Heritage

China’s dialect diversity reflects its vast geography and long history. As a traveler, understanding this linguistic landscape transforms your experience from observation to participation.

Whether you’re bargaining in a Guangzhou market, ordering tea in a Beijing hutong, or navigating Shanghai’s modern boulevards, language awareness enhances every interaction.

The next time someone asks if you speak Chinese, you might respond: “Which Chinese?” This simple question acknowledges the rich linguistic heritage that makes traveling across China such a remarkable journey.

Chinese dialects represent one of humanity’s greatest linguistic treasures—a living museum of language evolution spanning millennia. As China continues its rapid modernization, these dialect traditions face unprecedented challenges. Travelers who engage with this diversity don’t just enhance their own experience; they participate in honoring and preserving irreplaceable cultural heritage.

Our Travel China With Me tours incorporate dialect awareness into every itinerary. We believe understanding China’s linguistic landscape is as essential as visiting its physical landmarks. Each dialect tells a story—of migration, conquest, resilience, and cultural exchange. By listening carefully, travelers hear the echoes of Chinese civilization’s extraordinary journey through time.